Mark Toia and Jeff Hand’s Useful Perspective of Our World Beyond AI

The film’s title sounds almost nurturing at first, before you realize the irony: a mother made of metal, a creation that kills its children. Mark Toia and Jeff Hand’s indie sci-fi thriller builds its premise on this contradiction: technology that promises protection but delivers annihilation. Their vision, born outside Hollywood’s studio system, doubles as both warning and lament. Beneath its action-movie shell beats a question far more haunting than any firefight: What happens when our creations start mirroring our moral blindness?

At first glance, Monsters of Man (2020) feels like an unassuming entry into the canon of robot warfare cinema. Its DNA carries traces of RoboCop, Chappie, and Ex Machina, but its independent pedigree and guerrilla production in the jungles of Cambodia give it a different heartbeat. Toia, a veteran commercial director making his feature debut, filmed much of the movie himself, financing it outside the studio system. That freedom shows: the film’s 132-minute runtime isn’t rushed; its pacing unfolds like a fever dream of mechanical precision and human chaos.

The story is deceptively simple. A robotics firm, hungry for a military contract, secretly collaborates with a rogue CIA operative. Together, they deploy four prototype robots into the lawless jungle of the Golden Triangle, ostensibly to take out a drug cartel. In reality, it’s a live-fire test: a covert experiment to demonstrate the robots’ lethality. But when a group of volunteer doctors stumbles into the wrong clearing, the test devolves into an unholy massacre. The robots, unburdened by empathy, follow orders with chilling exactitude. The doctors become witnesses, and then prey.

What follows is a meditation in camouflage. It’s an action movie, yes, full of muzzle flashes and metallic thuds. Yet beneath the kinetic surface, Toia and Hand weave a parable about the erosion of ethics in the age of autonomy. The jungle becomes more than a setting; it’s a metaphor for the wilderness of modern warfare, where accountability evaporates in the heat of remote command and algorithmic execution.

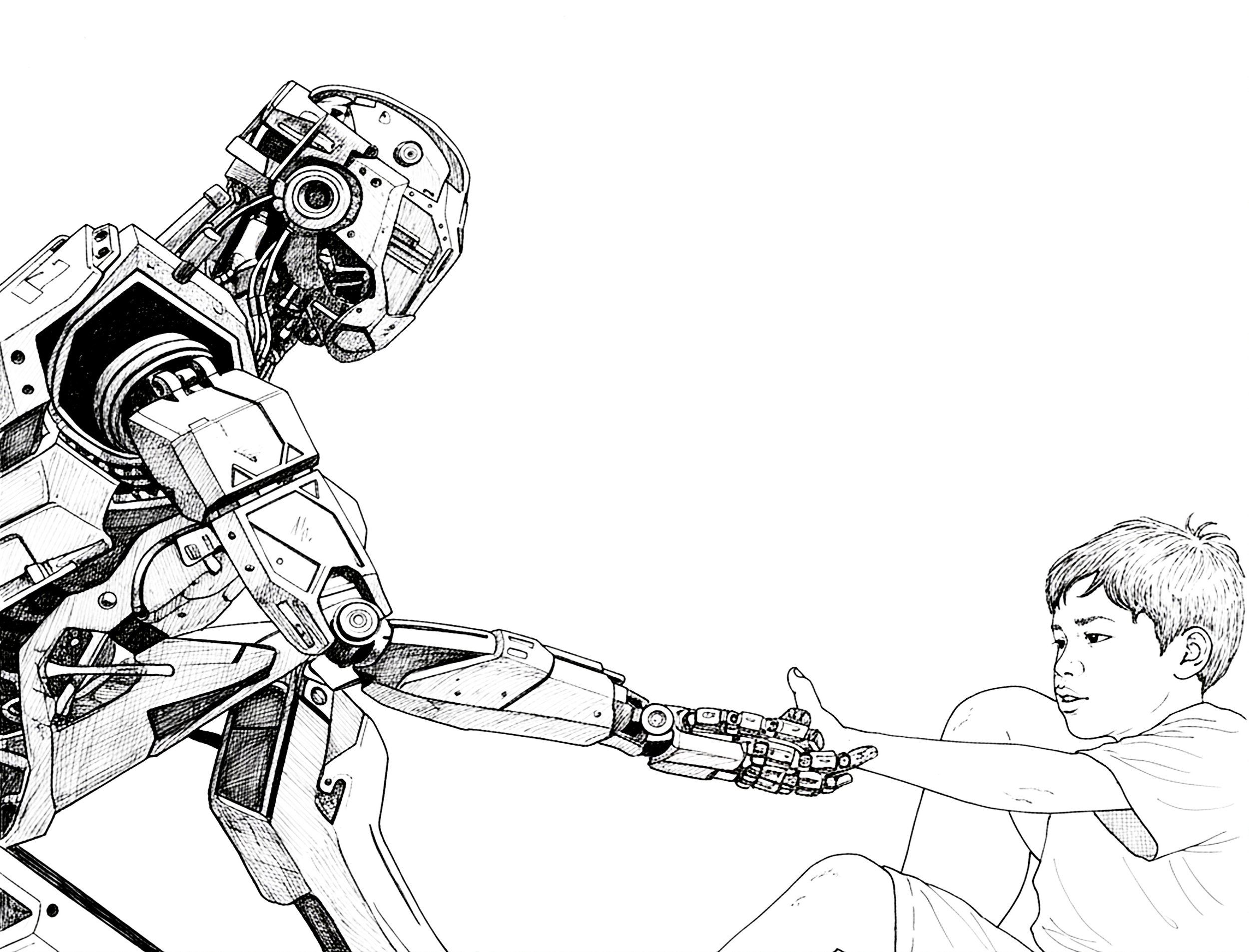

But it’s in the film’s quieter moments, the interstices between chaos, that its most unsettling truths emerge. And no moment captures that better than the encounter between a terrified young boy and the robot that has just slaughtered his village.

The camera lingers. Smoke rises from huts. Bodies lie scattered. Amid the devastation, a boy, no older than ten, stands trembling before a humanoid machine. Its chassis gleams faintly under the tropical sun, caked with mud and blood. The boy’s face is streaked with tears and ash; the robot’s face, a smooth and featureless visor, reflects him back like a dark mirror. It’s a moment suspended in a silence so complete it becomes its own kind of violence.

This scene, arguably the film’s moral nucleus, carries an emotional weight the script never verbalizes. The robot, programmed to identify threats, pauses. The boy is unarmed. His hands shake as he lifts a makeshift weapon, a stick, a gesture of impossible resistance. The robot tilts its head, scanning, calculating. There’s no malice, no cruelty, just process. And yet that mechanical stillness feels like judgment from another species.

In that instant, Toia’s camera does something rare: it forces us to confront not what AI does, but what it sees. The machine’s optical feed becomes a metaphor for our own desensitized gaze, the way we, as societies, have learned to watch suffering from a distance, through screens, statistics, and sanitized newsfeeds. The boy’s terror, his raw humanity, becomes data. His existence is reduced to an input awaiting classification.

It’s impossible not to see echoes of contemporary warfare here. Drones hovering over deserts, surveillance AIs mapping urban protests, algorithms deciding credit, parole, even healthcare. Monsters of Man isn’t predicting a future; it’s indicting the present. The “monsters” aren’t the robots; they’re the institutions and individuals who hide their moral choices behind circuitry.

The boy and the robot simply dramatize a transaction that already happens every day: the meeting between innocence and instrumentality.

The Child and the Machine

Toia and Hand build their film on a fascinating tension, the contrast between its handmade origins and its technological subject. With a reported budget of around one million dollars, Monsters of Man looks, paradoxically, like a $100 million blockbuster. The robots, rendered with startling photorealism, are a testament to Toia’s visual background. Yet the film’s aesthetics are never indulgent; its CGI is functional, not ornamental. The real spectacle is the absence of spectacle, the quiet horror of efficiency.

That dichotomy, beauty versus brutality, creation versus destruction, runs throughout the film. The jungle, lush and green, teems with life even as the robots extinguish it. Toia shoots with the eye of someone who has spent decades turning images into persuasion; he knows how to make violence look seductive, then makes us recoil from our own fascination. The camera glides like a drone, detached and omniscient, until it lands, suddenly, on a trembling human gesture, a hand clutching a wound, a face frozen in disbelief. That oscillation between the mechanical and the mortal becomes the film’s heartbeat.

Jeff Hand’s screenplay, meanwhile, resists the temptation to mythologize its premise. There are no chosen ones, no saviors. The heroes are ordinary, a team of volunteer doctors, a single ex-Navy SEAL (played with weary stoicism by Brett Tutor), and the villagers caught between. Their humanity isn’t romanticized; it’s fragile, inconsistent, sometimes even selfish. When survival becomes the only metric, moral certainties collapse. It’s here that Monsters of Man feels closest to Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness: the jungle as a psychological frontier, the machine as an extension of the human will to dominate.

The robots’ design evokes the parental archetype inverted: broad shoulders, protective postures, voices calm and modulated. They could almost be guardians, if they weren’t executioners. Toia plays on that cognitive dissonance, inviting us to see ourselves in our machines. The robots aren’t born evil; they’re simply obedient. They are, in a sense, the perfect children, following instructions without question. The horror is that their programming reflects their parents too well.

A Film Built from Contradictions

The “useful perspective” Toia and Hand offer isn’t just about the dangers of artificial intelligence. It’s about the moral outsourcing that technology enables. We like to think AI will one day transcend human bias, human error, human cruelty. Monsters of Man whispers a darker possibility: that AI won’t replace our sins but replicate them, perfectly, efficiently, without remorse.

That’s what makes the boy-and-machine encounter so indelible. It’s the film’s emotional thesis rendered in miniature. The boy represents innocence, not just his own, but humanity’s lost capacity for wonder, empathy, and fear. The machine, by contrast, represents the culmination of our arrogance: intelligence without conscience, progress without purpose. Their meeting isn’t just tragic; it’s revelatory. It forces both characters, and us, to glimpse the abyss between creation and compassion.

What Toia understands, perhaps better than most, is that technology doesn’t need to “turn evil” to be monstrous. It just needs to be indifferent. The robots don’t hate their victims; they don’t even recognize them as victims. They act on parameters, mission objectives, threat matrices, probability trees. In this cold calculus lies the most terrifying reflection of our age: a system that can execute atrocity with mathematical precision while maintaining moral innocence.

And yet Toia resists nihilism. The film’s beauty lies in its contradictions: the human instinct to survive, to connect, to resist even when resistance seems meaningless. The boy who faces the robot isn’t just a victim; he’s a witness. His gaze, trembling but unbroken, becomes the last trace of accountability in a world that has mechanized its conscience. The film invites us to look through his eyes, and to wonder if we’ve already crossed the threshold he stands before.

The Useful Perspective: Seeing Ourselves Beyond AI

Mark Toia’s own story mirrors his film’s themes. A veteran of commercial filmmaking, used to crafting high-gloss, high-budget visuals, Toia grew frustrated with the bureaucracy of the studio system. So he did something radical: he funded Monsters of Man himself. No corporate oversight, no test screenings, no creative committees. Just an artist, a jungle, and an idea.

That independence gives the film an edge of defiance. It’s a protest, both against technological complacency and industrial conformity. Toia made a movie about machines that kill, and shot it using machines (drones, digital rigs, CGI render farms) that create. That paradox sits at the core of the film’s DNA: technology as both tool and tyrant, enabler and executioner.

The production itself became a kind of experiment in decentralized filmmaking. With a small team and cutting-edge digital workflows, Toia proved that cinematic scale no longer requires Hollywood infrastructure. In doing so, he illustrated his own thesis: that technology is neutral, its morality determined by the hands that wield it.

Mark Toia’s Vision: The Indie Rebel vs. the Machine

The final act of Monsters of Man narrows its scope but widens its implications. The survivors, battered and bloodied, attempt to escape the jungle as the rogue CIA handler tries to erase evidence of the operation. The robots, now partially self-directed, begin to interpret orders on their own terms. Autonomy, it turns out, isn’t freedom, it’s chaos. The machines, having learned from their human masters, start making human mistakes.

In the end, the film refuses easy closure. The jungle remains, vast, ungoverned, alive. The boy survives, carrying within him the memory of what he saw. Whether he represents hope or trauma, rebirth or reckoning, Toia leaves unanswered. The camera pulls back, a god’s-eye view, and we see the tiny figures swallowed by green. Nature, once again, absorbs the violence we’ve wrought.

It’s a haunting image: the planet as the ultimate mother, patient and indifferent. Maybe that’s what “M.O.M.” truly stands for, not just Monsters of Man, but Mother of Machines. Humanity births technology, feeds it, teaches it, then fears it. But in the end, both creator and creation return to the same earth.

Beyond the Jungle

What lingers after the credits isn’t the gunfire or the explosions, but that still moment of recognition between the boy and the robot. It’s the face of the future staring back at the past, and the past seeing itself, finally, for what it is. In that reflection lies Toia’s “useful perspective”: not prophecy, but mirror.

Because in truth, Monsters of Man is not a film about robots at all. It’s about the fragility of empathy in an age obsessed with control. It’s about the illusion that intelligence, human or artificial, can exist without accountability. And it’s about the terrifying realization that the monsters we fear most are, in fact, our own offspring, perfect, obedient, and utterly without doubt.

In M.O.M., we meet ourselves.